Suzi often sends me photos of her hiking in beautiful Switzerland. It’s an activity that I encourage all my ladies to do if possible, not only because of the benefits to our mental health when we are out in nature, but because a good hike, using hiking poles, is beneficial to our ageing bones.

Hiking is an exercise strategy that over 30 years ago, when I pioneered the personal training industry in New Zealand as one of the very first Personal Trainers for the global giant of the fitness industry, Les Mills World of Fitness, I wasn’t promoting at all to my midlife clients.

Every day, I was putting mid-life women through their paces – sometimes it was cardio-focused, as well as some weight training, but I wasn’t promoting the balance and gait strengthening strategies that hiking on uneven surfaces gives women.

Nor in my past life, did I talk to these women about whether they were in menopause, nor if they were sleeping, or if they had a lot of stress in their lives, or how their gut health was.

Nor did I know to enquire about their nutritional intake in terms of the amount of pro-inflammatory foods they were eating. The research hadn’t yet caught up with what was really going on with bone health, diet, exercise and of course, the role of inflammation as we transition menopause.

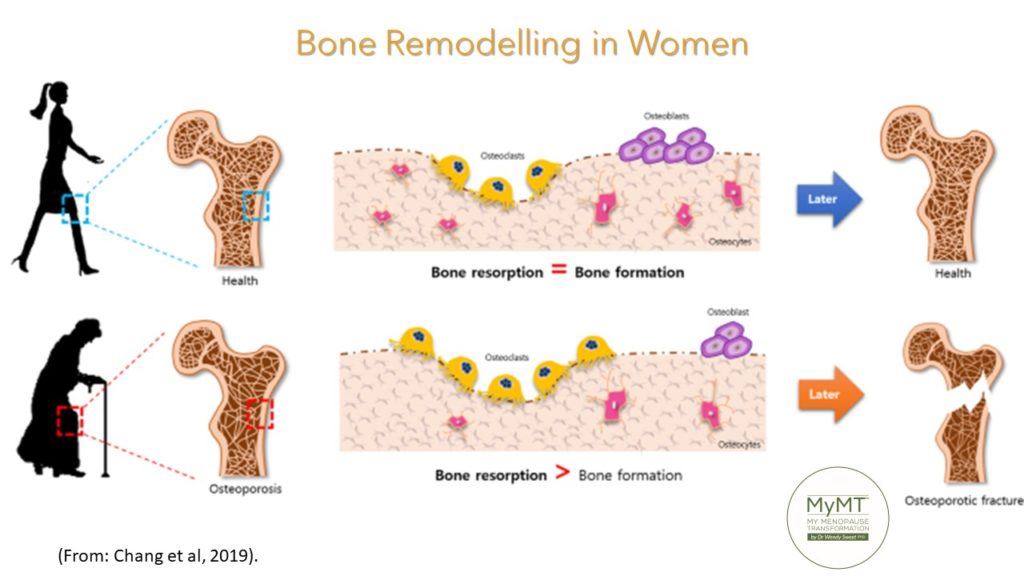

The trajectory towards osteoporosis in older age is an interesting one for all of us to take note of.

Not only does it start earlier than we think (peak bone mass occurs in our 30s and starts to decline from this point), but throughout the past few decades as we’ve been menstruating, the cycling of progesterone has played a dominant role in the remodelling of bones.

During our menopause transition, with declining levels of oestrogen and progesterone as well as changing cortisol levels, (this chronic stress hormone is elevated generally, if women aren’t sleeping or are feeling stressed), bone loss may speed up.

When cortisol levels are high, then so too are our inflammatory markers and whilst bones do need to be stimulated to generate some inflammation in order to re-model themselves, too much inflammation in the body can be problematic to our bones and the bone cells may not turnover, remodel and renew as readily as they used to.

Your skeleton is a metabolically active organ. Not only is it influenced by the amount and type of exercise you do throughout your life course, but new research shows that the density of bones as we age, is also influenced by the acidity of our diet (Osuna-Padilla et al, 2019) and whether we have too much (or not enough) inflammation accumulating in our body (Epsley, Tadros et al, 2021).

Bone Re-Modelling Must Be Stimulated as we Age:

Bone re-modelling is the continual process to renew the adult skeleton through the sequential action of osteoblasts (mediators of new bone cells) and osteoclasts (mediators of the continuous destruction of bone). Balance of both is key. This differs from bone modelling, which is responsible for skeletal developtment, growth and the shaping of bones in our early years. Hence, bone re-modelling (tissue breakdown AND repair) must be stimulated as we age. Through correct exercise, sleep, diet and of course, not having too many factors that cause the accumulation of too much inflammation (e.g. not sleeping in menopause), are important factors to pull together as we age.

As women live longer, degenerative skeletal diseases, such as osteoporosis, become increasingly prevalent. Over 50% of women reaching 65 years of age will experience a bone fracture (Teitelbaum, 2011), and if this has happened to you (as it has done to me as well), then you will understand the profound personal, financial and social impact of experiencing a fracture in mid-life, let alone the overall impact of osteoporosis in older women, on society as whole.

My private coaching group was abuzz with comments from hundreds of women around the world, when I decided to take a look down the road of acid versus alkaline foods and how the types of foods we eat in mid-life affect so many health concerns, that are given the generic label of ‘menopause symptoms’.

Bone density came into the conversation too – and it wasn’t just about bone enhancing exercise, it was about the role of too much inflammation in our body (measured by your blood bio-marker, called C-reactive Protein) and the acidity of diet too.

When I went into my own menopause transition, I knew about the prevalence of sarcopenia (muscle loss) and osteoporosis (bone loss) in older women. Hence, I was exercising, doing some resistance training, and trying to eat a diet high in calcium and proteins from dairy products and meat which, at the time, was recommended. However, before I did my women’s health and ageing studies, I never gave any thought to the fact that my body felt so ‘achy’ and inflamed, (despite all the supplements I was taking), because my diet may have been making my body more inflamed.

That’s because it was high in acid load.

Diet composition has long been known to influence acid–base balance by providing acid or base precursors. In general, foods rich in protein, such as meat, cheese, eggs, and others, increase the production of acid in the body, whereas fruit and vegetables increase alkalis.

The capacity of acid or base production of any food is called potential renal acid load (PRAL). Diets high in PRAL induce a low-grade metabolic acidosis state, which is associated with the development of metabolic alterations such as insulin resistance, diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, bone disorders, low muscle mass and other health complications as we age.

I was reiterating to women on my programme to keep up with the dietary changes that I promote, because over time, these will have positive benefits to their bone and muscle health as well as reducing symptoms and weight.

Health and ageing research is increasingly reporting that diet contributes to the accumulation of inflammatory changes in our body, and for women transitioning menopause, the chronic consumption of acidifying diets may cause a decrease in bone mineralization and an increase in bone fracture.

Hence, nutritional status is important for your bone health. So too, is your gut health. Inflammation in other parts of your body and nutritional status are not mutually exclusive, states brand new research on bone health and inflammation (Epsley, Tadros et al, 2021). As the authors state,

‘Chronic inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract (e.g. coeliac disease) are frequently associated with poor nutritional status, largely having to do with a reduction in caloric intake and difficulty in absorbing nutrients important to bone metabolism. Moreover, the gut microbiota plays a role in systemic inflammation via the immune system and meal ingestion can influence bone remodeling.’ (p. 2).

Absorption of Nutrients is Crucial to your Bone Health:

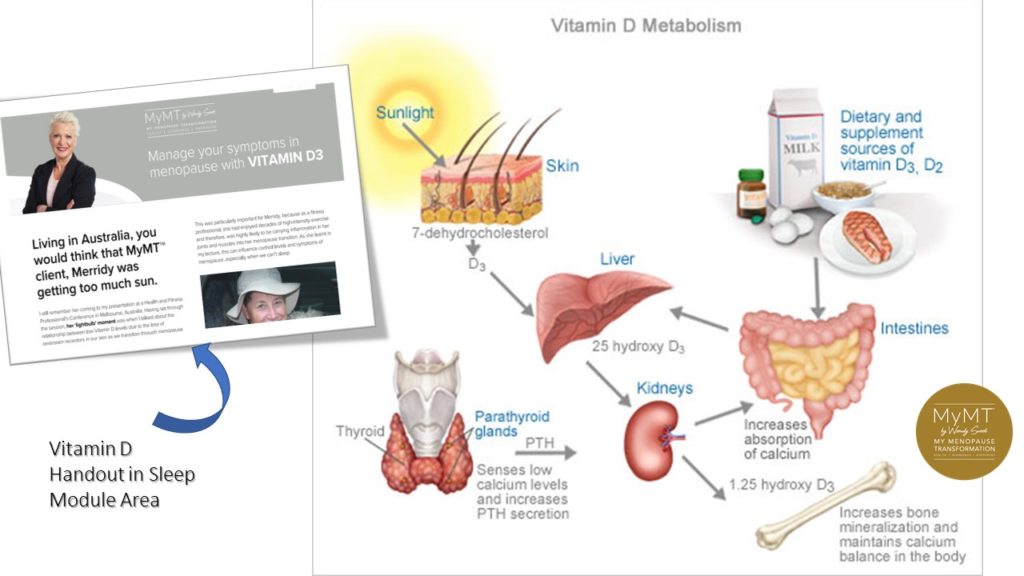

The absorption of nutrients in our ageing digestive system is a crucial part of the menopause-osteoporosis-inflammation connection. It’s why, as part of my programmes (and also available as a stand-alone programme), I have a module called ‘Restore your Grateful Gut. Both calcium and Vitamin D help in the re-mineralisation of bone and these nutrients are crucial in maintaining adequate mineralization of bone.

If these minerals are low, or if women are doing too much heavy exercise and not eating enough of the right foods, then they can tip over into thyroid problems, especially parathyroid over-activity. The body responds to deficiency by increasing parathyroid hormone (PTH) secretion.

With the winter well under way in the southern hemisphere, exploring your Vitamin D intake (and getting blood levels checked) is important. Vitamin D modulates your immune system. Vitamin D has also demonstrated an anti-inflammatory role in diseases, such as kidney disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Hence, low levels of vitamin D are correlated with a greater degree of inflammation in these conditions. (Epsley, Tadros et al, 2021).

Osteopenia needs to be on our radar too. It’s a condition that occurs when there is an imbalance between bone resorption of minerals and bone formation. Essentially, it’s the early stage of osteoporosis but doesn’t necessarily progress to full osteoporosis. There is great information on the Osteoporosis website in New Zealand and where-ever you live in the world, check out your local osteoporosis guidelines for your country as well. They are full of important information to have in your menopause-toolbox too.

But it’s not just about osteopenia and osteoporosis – the clinical names given to changes to our bones making them more brittle. There is another condition which hits us in menopause due to our changing reproductive hormones. This condition is the muscle-loss condition called SARCOPENIA.

Strengthening our muscles is not only important for us as we age, but the pulling and pushing of muscles on bones, helps in the process of bone re-modelling. The ends of your bones (the epiphysis) are where you get new bone cells forming and the epiphysis responds to pushing and pulling activities. Hiking downhill for example, can assist with knee joint strengthening (once you sort out your aching knees, which I teach you in the MyMT™ programmes).

These activities help to re-model the bone which then requires critical bone-building nutrients, such as Vitamin D, calcium, magnesium and phosphorous, to help healthy, new bone cells to be formed. But here’s the thing – hormonal changes in menopause, and other factors such as gut inflammation can inhibit the uptake of these vital nutrients into our bones.

Which is why we must remember that finding the balance between exercise, diet and rest and recovery is crucial to whether or not we accumulate too much damaging inflammation in our body. This is why, in the MyMT™ programmes, sleeping all night and improving health come before, adding in too much exercise. I’m always finding this in so many women, who are pushing through with exercise, but have underlying health concerns or aren’t sleeping.

I hope you can add in Osteoporosis prevention measures as you navigate menopause. Numerous factors impact this important health issue for women as they age and I cover all these factors in my programmes and in the 12 week ‘Rebuild My Fitness’ programme. Lifestyle factors which impact the trajectory of osteoporosis and sarcopenia, include,

1. Decreased physical activity as you age. If this is you, then now is the time to change this!

2. Decreased amino-acid (protein) intake and uptake due to changing liver inflammation. Proteins are ‘turned-over’ in your liver and if you aren’t absorbing adequate healthy proteins in your liver, then this can have a down-stream effect on sarcopenia and osteoporosis too.

3. Loss of activation of the motor-units (nerves) which stimulate muscles to contract. Muscle movement is controlled by your nervous and hormonal system and when we activate all of our muscles, then this is great for bone and muscle strength. It’s where the term ‘use it, or lose it‘ comes from. When your muscles are stimulated to pull on bones, then your bones are also stimulated to turn-over new bone cells.

4. Age-related decline in the hormones which assist your bones to stay strong, i.e. progesterone, testosterone, growth hormone, Vitamin D and IGF-1.

5. An increase in inflammation in other parts of your body. For example, gut inflammation can inhibit the uptake of key nutrients that support bone health as does not sleeping well overnight. If you aren’t sleeping, your body isn’t healing and repairing itself.

6. The wrong diet for menopause. A typical Western diet that is high in processed foods, sugar and alcohol is typically not osteopenia or osteoporosis friendly. It has a high acid load. This is why I say when it comes to menopause and the risk of oesteoporosis with age, we all need to improve our diet to better meet our changing hormonal environment which will become our ‘new-normal’ the older we get.

7. Being too thin or small in stature. If you have a thin bone structure, and weigh less than 62 kg, then you are at greater risk for osteoporosis as you get older. Your goal therefore is to increase your muscle mass and maintain a body weight that decreases your risk as you age.

Numerous factors impact on our bone health and muscle strength as we age. I know frrom the ladies on my programmes that whilst lack of time, low motivation and low energy are always the main barriers to being active, having a focus on turning these barriers around is a great starting point.

Then, we must use the right nutrition as well as the right exercise to stimulate bone turnover in a positive way, because as the World Health Organisation Bulletin (2003) on how to de-fuse the osteoporosis time-bomb reminds us –

‘Exercise minimizes bone loss later in life. Not only does exercise improve bone health, it also increases muscle strength, coordination, balance, flexibility and leads to better overall health. Walking, aerobic exercise, and t’ai chi are the best forms of exercise to stimulate bone formation and strengthen the muscles that help support bones. Encouraging physical activity at all ages is therefore a top priority to prevent osteoporosis.‘ [Chan, Anderson & Lau, (2003)]

I hope you can join me sometime on either of my different 12 week programmes which all place the scientific lifestyle evidence on women’s health as they age, at the heart of them.

Dr Wendy Sweet, Ph.D/ Member: Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine and Founder of MyMT™.

References:

Chan, K., Anderson M., & Lau, E. (2003). Exercise interventions: defusing the world’s oesteoporosis time bomb. [WHO Bulletin]

Chang, Y., Cho, B., Kim, S. et al. (2019). Direct conversion of fibroblasts to osteoblasts as a novel strategy for bone regeneration in elderly individuals. Exp Mol Med 51, 1–8.

Kruger, M. & Wolber, F. [2016]. Oesteoporosis: Modern paradigms for last centuries bones. Nutrients (8),376, 1-12.

Ginaldi, L., Di Benedetto, M. C., & De Martinis, M. (2005). Osteoporosis, inflammation and ageing. Immunity & ageing: I & A, 2, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4933-2-14

Lohana, C. & Samir, N. (2016). Risk Management of Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women. Global Journal of Health Science, Vol. 8, No. 11; 36-44

Osuna-Padilla I., Leal-Escobar G., Garza-García C., & Rodríguez-Castellanos F. (2019). Dietary Acid Load: mechanisms and evidence of its health repercussions. Nefrologia (Engl Ed), 39(4):343-354. English, Spanish. doi: 10.1016/j.nefro.2018.10.005. Epub 2019 Feb 5. PMID: 30737117.

Prior JC. (1990). Progesterone as a bone-trophic hormone. Endocr Rev. May;11(2):386-98. doi: 10.1210/edrv-11-2-386. PMID: 2194787.

Seifert-Klauss, V., & Prior, J. C. (2010). Progesterone and bone: actions promoting bone health in women. Journal of Osteoporosis, 845180. https://doi.org/10.4061/2010/845180

Teitelbaum S. L. (2007). Osteoclasts: what do they do and how do they do it?. The American Journal of Pathology, 170(2), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.2353/ajpath.2007.060834