What post-workout nutrition do you follow? Are you continually spending money on expensive supplements or protein powders? Are you confused about all the different advice on workout foods and amount of protein you need?

Protein intake is a topic that gets a lot of attention from the women on the MyMT™ programmes. Some are having too much, some aren’t having enough, and some find that advice from their Trainers conflicts with what I’m giving in my programmes.

The confusion is real. And I totally understand this myself, because despite teaching about protein as a macro-nutrient, in numerous lectures on Sport and Exercise Nutrition, I found that when I got to my early 50s, the amount and type of protein I was having after my workouts, was leaving me feeling tired, heavy, bloated and ‘gassy’!

Many ladies on my programmes were experiencing similar issues, which is when I went back to the books to explore protein intake … but this time, not for athletes, but with women’s healthy ageing and the menopause transition on my mind.

In 2019, the Lancet Medical Journal published a paper exploring the effects of animal proteins on human health. I became aware of the paper whilst listening to a session on high protein diets and the effect of these on longevity, whilst at a Lifestyle Medicine conference.

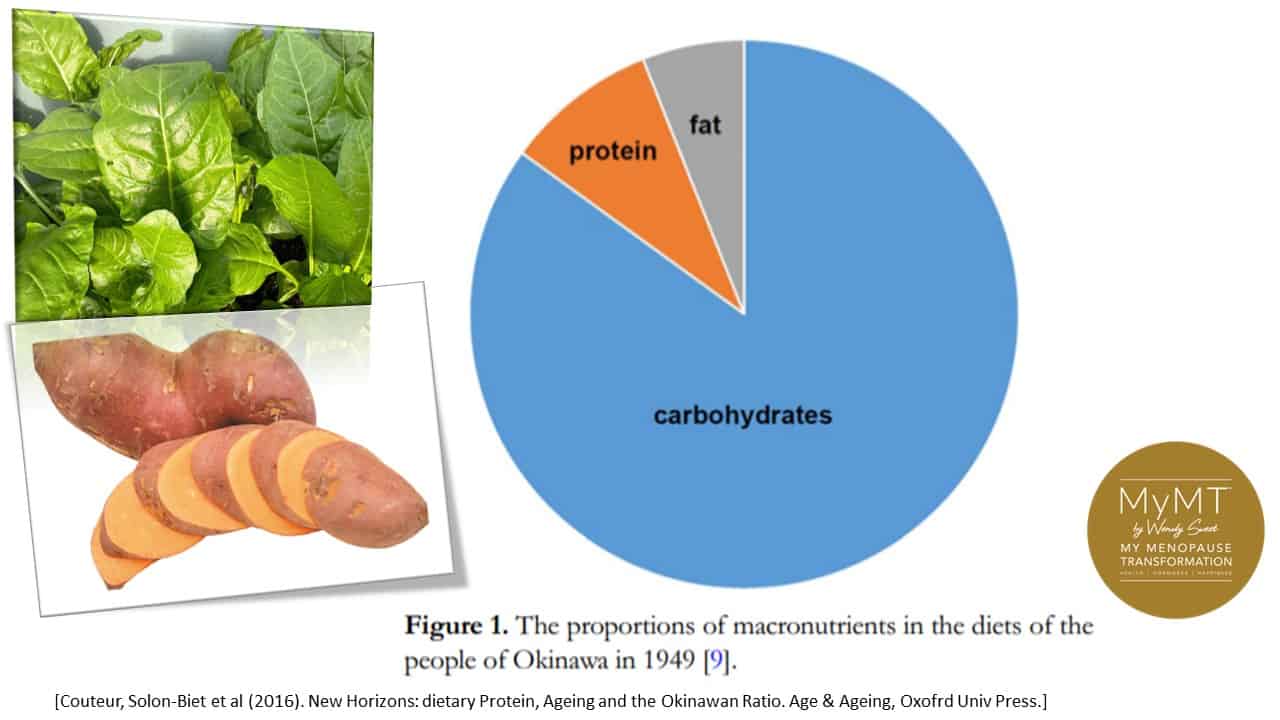

The presenter was discussing the Lancet paper (Kitada, Ogura et al, 2019) and sharing the findings that a lower protein (20-25% daily intake which translates to around 0.8 – 1.2 gm/kg/day) and high carbohydrate diet (50-60% daily intake) with an emphasis on plant proteins, plays a critical role in longevity and metabolic health.

Over the course of that day, I listened to another presentation on the Keto Diet. In this, the presenter was arguing his case for moving people towards a high-fat diet, sourced sourced mainly from animals. But of course, animal sources of food, are also high in protein.

Generally, popular ketogenic advice suggests an average of 70-80% fat from total daily calories, 5-10% carbohydrate, and 10-20% protein. For a 2000-calorie diet, this translates to about 165 grams fat, 40 grams carbohydrate, and 75 grams protein per day.

A few months later, I listened to a Sport and Exercise Scientist promoting a very high protein diet for women in menopause for bone health and prevention of sarcopenia (muscle loss). She was advocating heavy weight training and a daily dietary protein intake which equated to an intake of up to 2.2 gms/kg/ day or up to 2.4gms/kg/day.

For a woman in menopause who is around 80 kg this is anywhere between 176 gms of protein and up to 192 gms of protein daily in 25 gram servings.

The higher amount equated to around 8 x 25 gram servings of protein daily. There was no mention of whether that protein was animal protein, nor the effect on ageing kidneys. If it was animal protein, then this is also a high fat diet too. All animal protein contains high amounts of saturated fats.

These highly respected scientists were all promoting different ways of eating and they each had their validated research to back up their presentations. However, in each of these presentations there was an assumption about how much, or how little exercise people were doing. This is where protein intake may get confusing isn’t it?

On that particular day at the conference, I experienced similar confusion too.

With the utmost respect for all the academic experts presenting on dietary protein intake, and with the understanding that all women differ in their dietary protein needs especially depending how much exercise and the type of exercise they are doing, this was a pivotal moment in my own awareness.

Very simply, I realised that I needed to better understand the research as it relates to midlife women.

With my positioning of women’s mid-life menopause in women’s health and ageing science, it made sense to start by looking through this lens, rather than the sport and exercise lens or the weight-loss lens.

Acknowledging all these factors, and supported by studies on the ‘Okinawan Diet’ which supports 15-20% of our diet as protein, there is also a large body of new evidence from the International PROT-AGE Study Group and European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) which concluded that daily protein requirement of healthy individuals over 60 years is 1.0–1.2 g protein/kg/bw.

BUT a further increase is recommended for individuals with acute or chronic illnesses (1.2–1.5 g protein/kg/bw) and if adults have severe illnesses, injuries, or malnutrition then this may go up to 1.8-2.0g/kg/bw).

Protein content in the diet changes depending on various conditions. Therefore, protein intake can be increased or decreased because of health conditions or for specific targets of dietary interventions, such as the amount and type of exercise you do (e.g. heavy weight training versus yoga or walking). Don’t forget also, that dietary protein can also markedly influence food intake by affecting physiological and neurobiological regulatory mechanisms that help to balance both hormones and the thyroid function. [Pałkowska-Goździk et al, 2017].

So, my message to you is that when it comes to protein, the purpose of your intake matters.

This may depend on:

- the type and amount of exercise you do

- whether you have a physically active job (e.g. nursing or farming)

- whether you have fatty liver or an inflamed liver (amino acids from proteins are absorbed through the liver)

- if you have a healthy gut and pancreas which is where you produce enzymes to break down proteins.

- whether you are still menstruating or not. If you are menstruating then your protein intake needs to increase to 1.2- 1.4gm/kg/day

The World Cancer Research Fund’s 2018 report on the risks of meat, fish and dairy consumption and cancer, is interesting reading. It backs up a graph that I showed students a few years ago when lecturing about nutrition and cancer risk. The highest consumption of red meat in the world per capita is in Oceania (New Zealand, Australia, Polynesia and Micronesia) with America a close second. It’s hasn’t gone un-noticed by the World Cancer Research Fund, that these countries also have the highest incidence of colon cancer. (WCRF, 2018)

In the 1890s the USDA recommended over 110 g dietary protein per day for working men. Based on the belief that protein was the source of muscular energy (carbohydrates and fats are) and the observation that protein consumption was higher in the more successful (i.e., affluent) social groups or nations than elsewhere, the change in protein consumption began. But priority attention was really given to it in the 1950s and 1960s when the “World Protein Gap” was considered the major cause of infant mortality and retarded development in the Third World. It was deemed that this ‘problem’ could be solved by the application of sophisticated technology to enhance production of protein. So began the modern agricultural industry and the world demand for protein took off.

But there was something else happening by the end of the 1960’s and into the 1970’s as well. The increasing focus on body-image fuelled by the pioneers of the modern fitness industry – Joe Weider, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Charles Atlas. Images of protein-fuelled muscles intersected with the growth of magazines and media dedicated to how to get and maintain the ‘perfect’ body. By 1995, I was setting up Personal Training for the Les Mills group in Auckland. Surrounded in the gym by body-builders and rugby players such as the All Blacks, we were enthralled with the direction that America was taking in the fitness industry with the emphasis on a new 12 week programme by well known body-builder, Bill Phillips. It was called ‘Body for Life’. You could attain your ‘perfect’ body through disciplined attention to weight training, very little cardio and a diet that promoted protein. Lots of protein. In fact, up to 2.0 grams of protein per kg per day, set out in 20 gram portions throughout the day.

30 years later, after having my head in women’s health research, I would be able to look Bill in the eye and say, “It was your body Bill, not mine .. and it wasn’t for life.” Yes, like most stringent diet plans that emerged in the 1980 and 90’s, they just weren’t sustainable. They also weren’t designed for women who don’t have the ability to grow the amount of muscle that men do.

With sports nutrition and workouts on my mind this weekend as well as the fact that the All Blacks are playing in the rugby World Cup final, and they would enjoy this smoothie after their game too, I have this wonderful MyMT™ post-workout Smoothie for you to enjoy. It’s also high in calcium, and we need 1200mg of calcium daily, particular after a workout to help reduce muscle cramps.

There’s not a processed protein powder to be found, but instead, whole nuts, low-fat yoghurt and delicious purple grapes, a source of the anti-inflammatory compound called Resveratrol, which is found in concentrations in their skin. [Singh et al, 2016].

A MyMT™ Post-Workout Smoothie for you to enjoy:

My swim yesterday was a tough one. I pushed myself to get the combination of aerobic and anaerobic intensity that my body needed after a busy week of sitting at my computer doing numerous zoom presentations around the world.

When I got home, I made up this high-plant protein smoothie filled with delicious anti-inflammatory carbohydrates. Don’t forget that you need both carbohydrates and proteins in the first hour or so, after your workout because the carbohydrates help the protein to be taken up into muscles for recovery. I hope you enjoy it. The protein servings are an approximation based on 100 gm servings.

Ingredients:

- 1/2 cup of blanched almonds (approx. 10 gm protein)

- 1/2 cup of pistachio nuts (approx. 10 gm protein)

- Purple grapes – palmful

- 100 gms or 1/2 cup of low-fat Greek Yoghurt (approx. 4 gms protein and 125 mg of calcium

- Freshly squeezed orange juice of 1 medium orange (for Vitamin C)

- 1.5 cups of natural spring water (or enough for the consistency you need)

- 1 small banana (optional)

Place all in a blender or your Nutribullet and whizz away until you get the consistency that you like. Bon appetit!

References:

Le Couteur DG, Solon-Biet S, Wahl D, Cogger VC, Willcox BJ, Willcox DC, Raubenheimer D, Simpson SJ. New Horizons: Dietary protein, ageing and the Okinawan ratio. Age Ageing. 2016 Jul;45(4):443-7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw069.

Lonnie M, Hooker E, Brunstrom JM, Corfe BM, Green MA, Watson AW, Williams EA, Stevenson EJ, Penson S, Johnstone AM. Protein for Life: Review of Optimal Protein Intake, Sustainable Dietary Sources and the Effect on Appetite in Ageing Adults. Nutrients. 2018 Mar 16;10(3):360. doi: 10.3390/nu10030360.

Pałkowska-Goździk E, Lachowicz K, Rosołowska-Huszcz D. Effects of Dietary Protein on Thyroid Axis Activity. Nutrients. 2017 Dec 22;10(1):5. doi: 10.3390/nu10010005.

Schoenfeld BJ, Aragon AA. How much protein can the body use in a single meal for muscle-building? Implications for daily protein distribution. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2018 Feb 27;15:10. doi: 10.1186/s12970-018-0215-1.

Singh CK, Liu X, Ahmad N. Resveratrol, in its natural combination in whole grape, for health promotion and disease management. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015 Aug;1348(1):150-60. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12798.

Watford, M. & Guoyao Wu, (2018). Protein. Advances in Nutrition, 9 (5), 651-653,

ISSN 2161-8313