During the past few decades, numerous ageing and health studies have emerged discussing the link between lifestyle factors, inflammation and telomere dysfunction, yet much of the popular media advertising to our demographic, seems more intent on promoting a range of expensive remedies from supplements to skincare.

Many of these remedies don’t mention our ageing telomeres however, and the beautiful role of a compound called betaine, which is found in a variety of foods. Understanding the lifestyle factors that help us age more healthily is important, simply because it is well known in geriatric medicine, that women live longer than men. Seven years longer in fact.

This remarkable feat is mainly to do with the length of the telomeres and the role that inflammatory changes play in how quickly we lose telomere length with age. And yes, this all starts in our menopause transition.

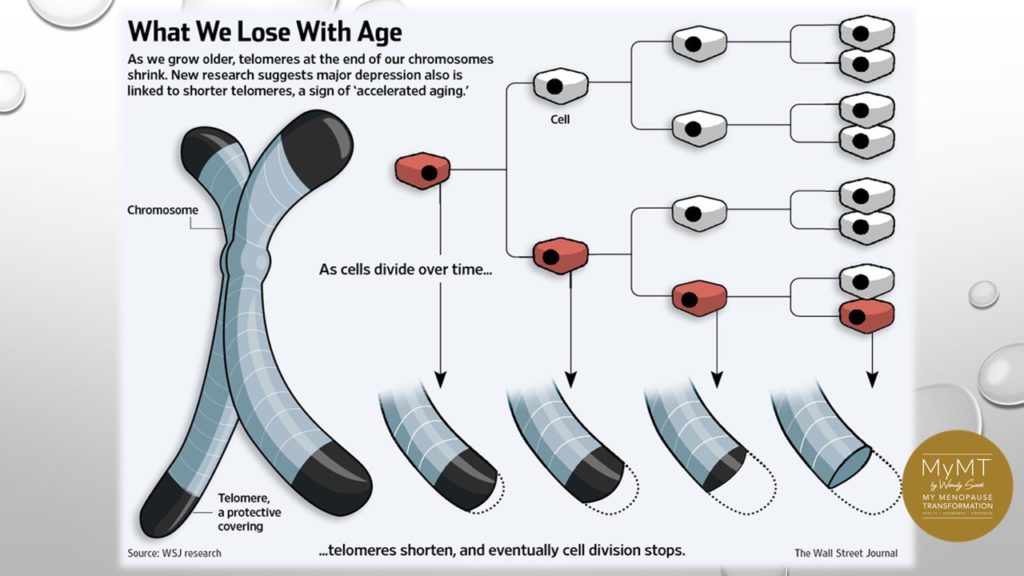

Telomere is the name given to the tiny ‘hard-helmets’ on the ends of each DNA strand. Thanks to Leonard Hayflick’s work on DNA in the 1960s, scientists now know that there is limited regeneration of each telomere over the course of the human life-span. This is called the ‘Hayflick Limit’. Telomere length at birth is similar in both genders, but women have longer telomeres later in life despite the fact that telomere length throughout life, has been shown to be hereditary from the paternal side (Nordfjäll et al., 2005).

Understanding ageing science and ‘how’ we age matters – especially when it comes to the length of telomere’s. Simply because there are things that we can be doing to reduce the rate of losing our precious telomeres and our menopause transition is the time to be aware of this.

In ageing science, the length of our telomere matters. Especially for women entering post-menopause and experiencing declining levels of oestrogen. Thanks to a fairly recent study of Finnish women, (Stenback, Mutt et al., 2019), it is now known that oestrogen and higher compatibility between mitochondrial and genomic DNA have been associated with higher Telomere length in women as they age.

Which surprises me.

Because it is well known that high stress levels (both psychological and oxidative stress from doing too much exercise or eating the wrong foods), are associated with shortened telomere length – especially in women.

If you’ve had a lot of stress over your life-time, and I not only include psychological stress in this statement, but physical stress from high amounts of exercise training too, then you might just need to change your lifestyle a bit to factor in protecting your terrific telomeres. There is a complex network influencing the maintenance and integrity of telomeres as we age, and this includes genetic, lifestyle, psychological and physiological factors.

All of these factors influence the level of inflammation that arrives as we move through menopause, and turning this around to promote healthy ageing is what I discuss in the MyMT™ programmes – our menopause transition arrives as the ‘perfect storm’ for changing levels of inflammation in the body.

With increasing inflammation from not sleeping, too much or not enough exercise, the wrong diet for our health as we age, becoming overweight and of course, from the incredible changes to our liver, gut and muscles during menopause, these are all detrimental to the length of our telomeres. As such, the rate of decline in our ageing is sped up.

But the good news is, with the right approach to your lifestyle in menopause, you can ‘age-well’ and slow down the rate of telomere shortening.

How can we slow down the rate of telomere shortening as we age?

- The right amount and type of physical activity matters.

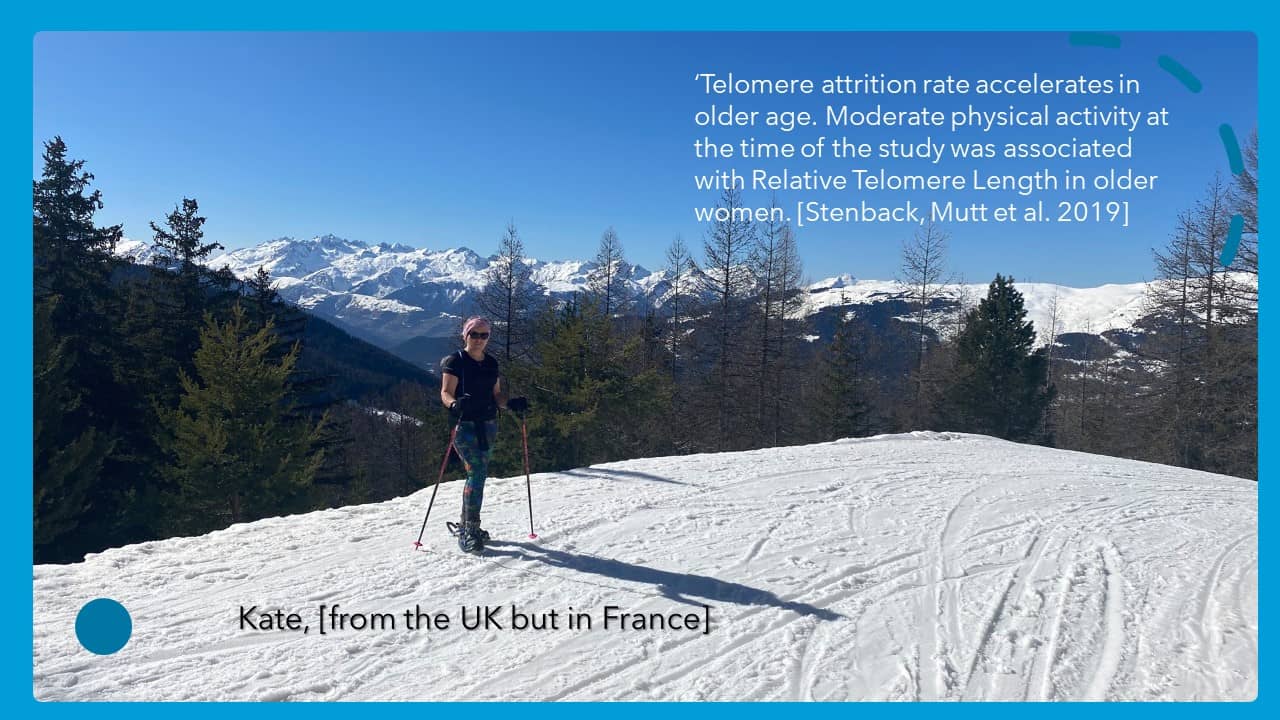

I love this image of Kate (below) who is on the Transform Me weight loss programme – at the start of last winter in the Northern Hemisphere, Kate was in France working as a ski-lodge manager with hubbie. The fact that the ski-fields weren’t fully operational, meant that she had more time to explore the Alps wearing her snow-shoes. Walking and hiking up hills are more moderate forms of exercise – and this is the type that helps to protect our telomeres as we age. Once she had turned around her sleep, joint health and lost 12 lbs, she was on her way to understanding how to exercise moderately, but not excessively, for the protection of her telomere length.

When, and if you can, adding in a couple of shorter sessions a week of more vigorous activity benefits us too – but as I’m always saying, only when you are sleeping all night and your joints are better. Up to 75 minutes of more vigorous activity each week helps to maintain telomere length, especially for those who are more highly stressed and enjoy the more vigorous workouts (Puterman et al., 2010).

One of the challenges for women in making sense of the marketing of ‘healthy ageing’ is knowing ‘how much exercise is enough?’ and this came through strongly on my own doctoral research. Many of the women relied on advice from the fitness and sporting industries which typically position ‘healthy ageing’ in higher intensity exercise and sporting feats, but this isn’t necessary. In fact, too much exercise training and competing is detrimental to the length of our telomeres – they become more inflamed.

Training for hours and over many years of practice at a professional level correlated negatively with Telomere Length (TL) in professional endurance runners (Rae et al., 2010). The same association was observed in competitive powerlifters; the TL in their vastus lateralis correlated inversely with the subject’s record in squat and deadlift (Kadi et al., 2008). These findings suggest an inverted U-shaped relationship between PA intensity and TL, with both high and low PA levels associated with shortened TL.

Stacey had this issue as well. Her passion for surf-lifesaving events led her towards the Masters event in Perth last year. Numerous emails between us, meant that not only did she cut back on some training, but she focused more on specific recovery for her ageing and changing joints and muscles. I include her heart muscle in this.

But what if you aren’t an exerciser or you can’t exercise because of your aching joints, your exhaustion or any heart health changes you are experiencing as you move through menopause?

Well, finding ways to move naturally and stay active is still important – not only to reduce the rate of telomere shortening, but to help reduce the rate of inflammation in your cells and tissues as well. This type of cellular inflammation is known as oxidative stress.

Numerous studies in ageing and health, report that sedentary people over the age of 50 years (men and women) are typically ageing faster – 9 years faster in fact, based on the rate of shortening of their telomere length, compared to people who are more active. As I mentioned above, subjects exercising with moderate intensity had the longest telomeres.

- Your food choices matter to telomere length.

The evidence over the past few decades that the Mediterranean Diet has emerged as an appropriate plant-centred dietary pattern that may affect women’s health as they age, to me, puts paid to any other dietary plan that women might be following. This is because ageing itself is known to be ‘inflammatory’ and as such, women moving through menopause into their ageing years, are at higher risk for shortening of the telomeres, because they are ageing. Add to this, not sleeping and/or feeling stressed and over-whelmed, then telomere shortening may be more rapid.

This is when diet becomes important.

Food compounds are known to affect the length of our telomeres including:

- Vitamin C

- Omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) which are balanced against Omega 6 foods.

- Foods high in polyphenols are known to be important for reducing the rate of telomere length – all of these types of nutrients help to reduce oxidative stress and inflammation (Preedy & Watson, 2019). For example, the intake of walnuts (organic preferably) reduce the rate of telomere length.

- Foods high in a compound called, Betaine. This powerful anti-inflammatory nutrient (found in beetroot, wholegrains, spinach and aquatic vertebrates), distributes primarily to the liver, kidneys and brain as well as muscles and reduces inflammatory changes in mitochondria. Betaine regulates energy metabolism and helps to relieve chronic inflammation.

I always know when a food compound is becoming important for our ageing, because invariably it gets marketed to us in expensive supplements. Betaine is no exception and along with choline, is now available as a supplement that we can take for ‘healthy ageing’. But menopause supplements are expensive and I often find that women on my programmes, don’t know why they are taking them and what they do. As well, many nutritionists remind us, that they are indeed ‘supplemental to our diet’. A factor I heeded when I realised that I was taking a lot of menopause-related supplements myself, but not changing my diet first and foremost!

Here in New Zealand, the National Nutrition Survey provides information on betaine intake in the average New Zealand diet. Males get more than women in their diet mentions the report and typically, glycine betaine is primarily found at high levels (⩾150 μg/g) in wholegrain products (wholegrain bread, pasta, flour), while proline betaine was found in fruit, especially oranges and orange juice and vegetables such as cruciferous vegies, spinach, beetroot and (to my relief) betaine is also found in coffee.

And then there is the role of nuts in helping to reduce inflammation – especially walnuts.

When we have busy lives and are always on the go, walnuts (and other nuts) not only give us energy, but new research on women’s health with age, report that walnuts especially, are rich in two types of fat called oleic acid and linoleic acid, and these both have anti-inflammatory properties. These types of fat are not only beneficial for our heart health, but also for our ageing telomeres as well.

Nuts are one of the main components of plant-based food that characterise the Mediterranean Diet.

Studies show that around ½ cup a day of a variety of nuts from walnuts to almonds, pistachios, peanuts and hazelnuts contain arginine (an important compound to help blood vessel dilation), folic acid (needed for ageing nerves), anti-oxidant vitamins and minerals such as calcium, potassium and magnesium (I wrote about magnesium in post-menopause HERE).

Reversing the effects of inflammation is important to all of us during our menopause and post-menopause years.

As I’m often saying in my newsletter articles to you, menopause symptoms aren’t just about our ovaries. Lowering oestrogen affects other organs around our body as well, including our muscles, heart, liver and other important organs.

This is why I’m passionate about women understanding that lifestyle medicine matters – from our exercise to our food to our sleep – ‘how’ we transition through menopause really does affect our health as we age. And for those women who are already experiencing health changes, it’s important to ‘turn back the clock’!

What to do is all part of the MyMT™ 12 week programmes of if you are a Health Practitioner, then please join me on January, 2024 for the next 12 week Health Practitioner Course. Please pre-register for the early-bird special HERE.

One of the foods that I have in the brand new updated Food Guides for each programme, is walnuts and my ladies know to try and get beetroot and other high-betaine foods into them too. If you are struggling to understand what to put into place and restore your health and energy, or if you are struggling to help your own midlife clients to navigate their menopause transition, then I invite you to come on board into any of these world-class online programmes when you can.

References:

Aubert G., Lansdorp P. M. (2008). Telomeres and aging. Physiol. Rev. 88 557–579. 10.1152/physrev.00026.2007

Egger, G. & Dixon, J. (2009). Inflammatory effects of nutritional stimuli: further support for the need for a big picture approach to tackling obesity and chronic disease. Obesity Reviews, 1-13.

Preedy, V. & Watson, R. (2020). The Mediterranean Diet: an evidence-based approach. Elselvier Academic Press: London, UK.

Rajaie, S., & Esmaillzadeh, A. (2011). Dietary choline and betaine intakes and risk of cardiovascular diseases: review of epidemiological evidence. ARYA atherosclerosis, 7(2), 78–86.

Slow, S., Donaggio, M., Lever, M., & Chambers, S. (2005). The betaine content of New Zealand foods and estimated intake in the New Zealand diet. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 18. 473-485. 10.1016/j.jfca.2004.05.004.

Stenbäck, V., Mutt, S. J., Leppäluoto, J., Gagnon, D. D., Mäkelä, K. A., Jokelainen, J., Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S., & Herzig, K. H. (2019). Association of Physical Activity With Telomere Length Among Elderly Adults – The Oulu Cohort 1945. Frontiers in physiology, 10, 444. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.00444

Stuart C., Betaine in human nutrition. (2004). The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 80(3), 539–549, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/80.3.539