Mountains feature a lot in the lives of many MyMT™ women. They feature a lot in my family’s life too. Whether hiking or skiing, we enjoy being in the mountains, as many women on my programmes do as well.

But it wasn’t always that way. One of the challenges that beset many of us as we transition menopause, is that simply, we have very little energy to enjoy the recreational activities that we have enjoyed for years.

As Jo mentioned to me, “In a previous life, I could not do a run at Mt Hutt (skifield in New Zealand), without stopping for a breather or to rest my limbs. I would have to go down to the car for a nap.”

So, why does this happen? Why are we suddenly drained of our energy levels as we move into and through menopause?

Part of the answer to this, lies in how our muscles and cells change as we move through menopause. And for those of you who are active, it’s important to understand why you may not be tolerating the activity levels or intensity of those activities, as you may have in the past.

Ageing has become an important topic for scientific research over the past decade, including muscular and strength research. With life expectancy and the number of men and women in older age groups increasing dramatically over the past few decades, interest has been growing about how we are ageing … as well as how to reduce the ageing-decline that many of our parent’s generation have experienced.

As such, muscle strength and function is an increasingly important area of research, because by 2050, the world’s population over 60 years will double from about 11% to 22%. This means that there will be 2 billion people aged 60 or older living on this planet. Approximately 400 million will be 80 years or older, over half of them women. I’m very passionate about you understanding how much your muscle strength and function change as you age and how this is impacting your energy levels as well.

My coaching community is full of women enjoying being active again. I say ‘again’ for a reason – many of them tell me that they have enjoyed activity all their life, but when peri-menopause arrived, aching muscles, insomnia, sore joints and fatigue, left them unable to do the exercise that they used to do.

There are numerous changes to our power-fibres in our skeletal muscles as we move into and through menopause. These are our Type-2 muscle fibres – the fibres that enable power, speed and jumping. Along with the loss of oestrogen in menopause, Type 2 power and speed muscle fibres diminish the fastest. It’s why many of you see your muscle tone and size decrease with age.

For those of you who are skiers, or runners or you like the harder, faster activity in your gym classes, or you are athletes, then this is why your recovery may be taking longer afterwards, or your legs and muscles ache all the time. This happened to me as well.

It took me a long time to figure out why I wasn’t able to do the harder, more powerful skiing that I used to be able to do. But as soon as I looked at menopause through the lens of our biological ageing, I knew I would find the answer when I better understood what happens to our muscles as we age.

Women’s muscle fibres comprise different ratios of fibres compared to males. There are two general types of fibres – slow twitch and fast twitch.

Slow twitch fibres are our endurance fibres and are known in muscle physiology terminology as ‘Type 1’ fibres.

Fast twitch fibres are our power and speed fibres and these are known as ‘Type 2’ fibres.

For women used to being active, these muscular changes are important to note, because the reduction in muscle fibre number and size is fibre type specific. We can lose anywhere between 10%–40% of our smaller Type-2 fibres and as I said earlier, this loss in these fibres, means that we also lose our power and speed fibres more than the Type 1 fibres that help us with our stamina and endurance.

It’s possibly the reason that many physical activity studies looking at older women’s exercise participation reports that walking (not running, jumping or sprinting) is the most popular activity as they age.

Furthermore, women in their 50’s are also the highest cohort to drop out of activity as they age. I’m not surprised that lack of energy, lack of time and lack of motivation are often cited as reasons to their decreasing participation. [Women’s Midlife Health, 2015].

But there’s more to understand about our muscle function as we go through menopause too.

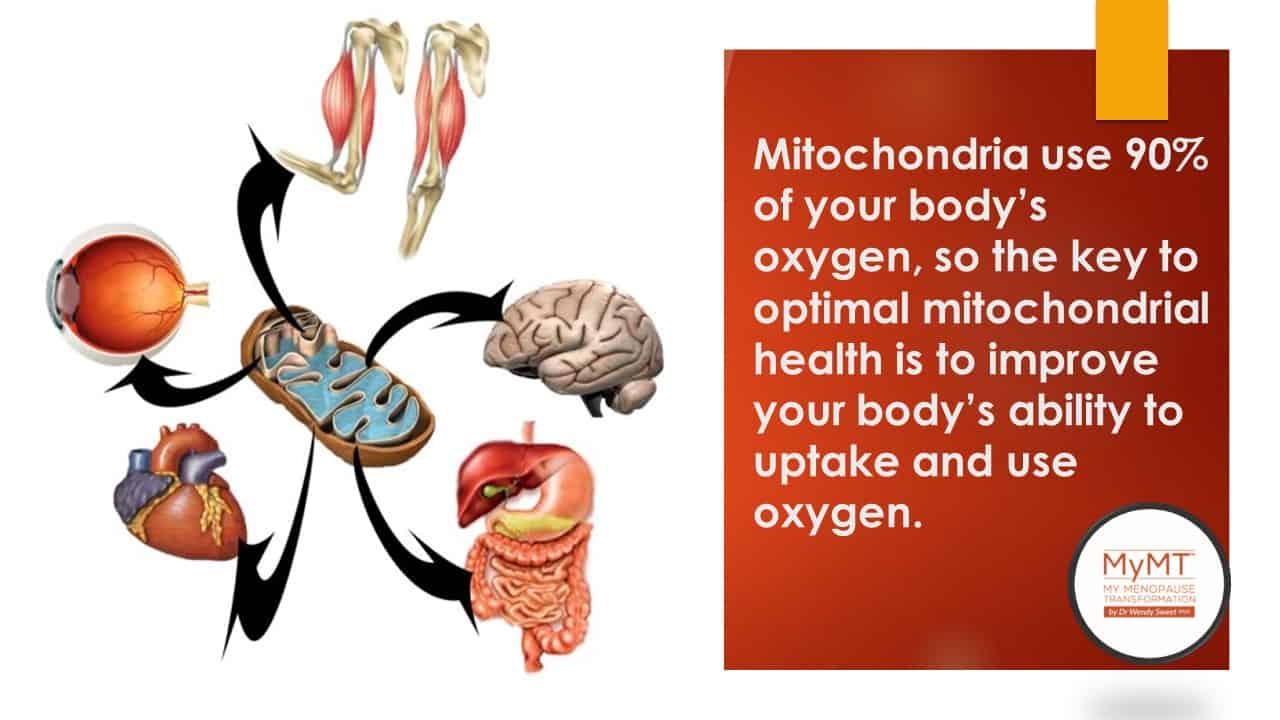

And it’s to do with our beautiful mitochondria.

Researchers are finding that when it comes to our metabolism, energy production, immune health repair and regeneration, our tiny mitochondria matter. As we move through menopause and age, we are losing muscle. When we lose muscle, we also lose numbers of our powerful little mitochondria.

The natural death of our mitochondria has been postulated as one of the mechanisms associated with muscle fibre loss with ageing.* As such, we need to be looking after these organelles that are so important to energy production. We also need to retain our mitochondria in muscle cells to help to prevent muscular weakness and loss of function as we get older as well as help our immune health.

For those of you, like me, who also want to retain your ability to enjoy physical recreational activities such as skiing or running, then you need to sleep well, improve your liver and gut health (this is so you absorb the nutrients that your muscles need to heal and repair overnight) and do the correct exercise that helps you to not only prevent muscle loss which in turn, helps you to prevent your mitochondria loss.

One way to achieve this, is to improve your energy and motivation for aerobic exercise as well as make the time to do it!

A lack of exercise decreases the efficiency and number of mitochondria in skeletal muscle, while exercise promotes mitochondrial health. So, if you want to retain some of your power and strength fibres (Type-2 fibres) as well as improve your Type 1 endurance fibres, then a combination of aerobic endurance and strength/ resistance exercises matter.

Mixing up the variety of exercise that you do is important as we get older.

This is because different types of exercise can trigger variable but specific responses in the muscle, especially when different nerves are stimulated. For example, the most important activity to do for improving mitochondrial function is actually steady-state aerobic exercise.

This is also important for fat-burning. Steady-state aerobic exercise is the type of exercise which you can do rhythmically for 30-60 minutes.

Strength training is also important as we age and is important for building or retaining the muscle that you do have. Then, once you are sleeping and have restored your energy levels, doing a little bit of high intensity interval training [HIIT] within aerobic exercises such as cycling and walking also has a positive effect at the cellular level at combating age-related muscle loss and weakness. This is why the 12 week Rebuild My Fitness programme takes you through a progressive improvement in your fitness levels over the 12 weeks (or longer) and numerous women stay on with me to do this programme after they have their symptoms, sleep, weight and sore joints sorted!

Age-related muscle loss and weakness is a combination of all of these factors, but more and more research is showing that muscle and mitochondria can be re-trained and retained through exercise.

Active elderly people have more of these mitochondrial cells than more-sedentary individuals do. This is also the reason why exercise prior to hip and knee surgery can speed up recovery in the elderly too.

The good news for women is that exercise can stave off and even reverse muscle loss and weakness with age. Physical activity can promote mitochondrial health, increase protein turnover in muscles, thus aiding repair, and staying active restores nerve signaling involved in muscle contraction and function.

And for many of you who don’t have the time to exercise, you don’t need to do as much as what was once thought – 30-60 minutes around 5 times a week is enough to help you age healthily and maintain good cardiovascular health.

When I felt too exhausted to do the exercise that I loved to do and it was no longer helping my weight management, I was so pleased that I had undertaken my doctoral studies on women’s healthy ageing.

It led me down the path towards better understanding about how our body changes when we don’t have the production of oestrogen and progesterone any more. The effect of losing these two hormones on our muscles, tendons and joints as well as our heart is more important that we’ve known in the past.

But as the first generation of women to be enjoying exercise and sports right into our menopause years, I also began to understand that everything that is being taught to exercise professionals in many exercise and sports courses has to date, been targeted towards younger populations, athletes and males.

Very little is taught about exercise that is specifically aimed at women’s hormonal health, especially in menopause. I realised that this is because women in their 50’s today, are the first generation to have aged alongside the modern fitness industry, so exercise prescription messages (and research) are lacking.

This is why I designed and developed the 12 week online Re-Build My Fitness Programme which you can do as a stand-alone programme or if you aren’t sleeping and/or have weight concerns, then I recommend you do the foundation programmes (either Circuit Breaker or Transform Me) first.

There’s never been a better time to focus on our health as we get older, and all my programmes are on sale for you with NZ$50 off. If you are keen to come on board on any of the programmes, then please enter the PROMO code, ATHOME23 into the link on the image below which takes you to my website and there is a description of the programmes and videos. I can’t wait for you to join me.

References:

Brunner, F., Schmidt et.al. (2007). Effects of aging on Type II muscle fibers: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Ageing & Physical Activity, July;15(3):336-48.

Butler-Browne, G., Mouly V., et al, (2018). How Muscles Age, and How Exercise Can Slow It. The Scientist Online Edition.

Lachman, M. (2015). Midlife as a pivotal period in the life course: Balancing growth and decline at the crossroads of youth and old age. Int J Behav Dev. January 1; 39(1): 20–31.

Miljkovic N., Lim J., Miljkovic I., Frontera W. (2015). Aging of skeletal muscle fibers. Ann Rehabil Med. Apr;39(2):155-62. doi: 10.5535/arm.2015.39.2.155.

Pierre, T. & Pizzo, P. (2018). The Ageing Mitochondria, Genes, 9, 22; doi:10.3390/genes9010022