It is becoming better known in lifestyle medicine that diet influences menopause symptoms and women’s health.

The diet that influences these factors the most, including reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases such as Type 2 Diabetes and abdominal obesity, is the Mediterranean Diet. [Vetrani, Barrea et al, 2022].

That’s why interest has been growing in the compounds in foods that are common in the Mediterranean diet, including the role of lycopene, which is found in numerous red and orange foods.

Tomatoes both raw and cooked are extensively consumed in the Mediterranean regions. Tomatoes are low in fats, rich in vitamins A and C, folate, potassium, carotenoids such as lycopene and polyphenols.

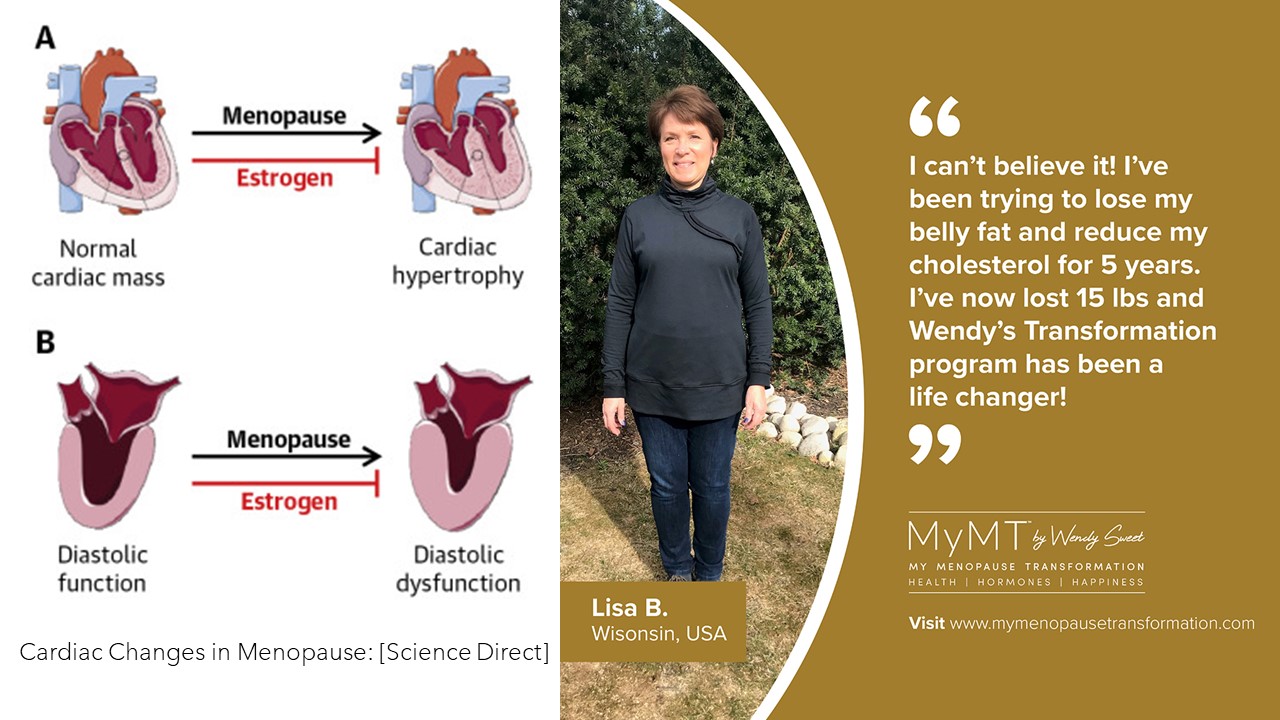

All of these nutrients are beneficial for women looking to reduce menopause symptoms as well as manage cholesterol changes, cardiac health, liver health, including Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). This is often a major contribution to weight changes during menopause. [Rovero-Costa et al, 2019]

I love the smell of the vine-ripened tomatoes coming off my vine at the end of summer. Tomatoes also feature in the Italian Tomato Sauce recipe which is in the MyMT™ Recipe Book in my programmes.

One cup (240mL) of tomato juice provides approximately 23mg of lycopene, which is evidenced to help in menopause and post-menopause cardiovascular and liver health. (Petyaev, 2016).

However, when it comes to the release of the lycopene from the tomatoes as well as enabling the body to absorb this powerful compound, this is optimal when tomatoes are cooked. Heat transforms natural lycopene to a form that is easier to utilize by the human body.

Understanding that liver and gallbladder detoxification pathways respond to certain foods, was a key part of my own weight loss, and it’s why I include this information in the MyMT™ Menopause Weight Loss Coach Course for you, which is on sale throughout the month of October.

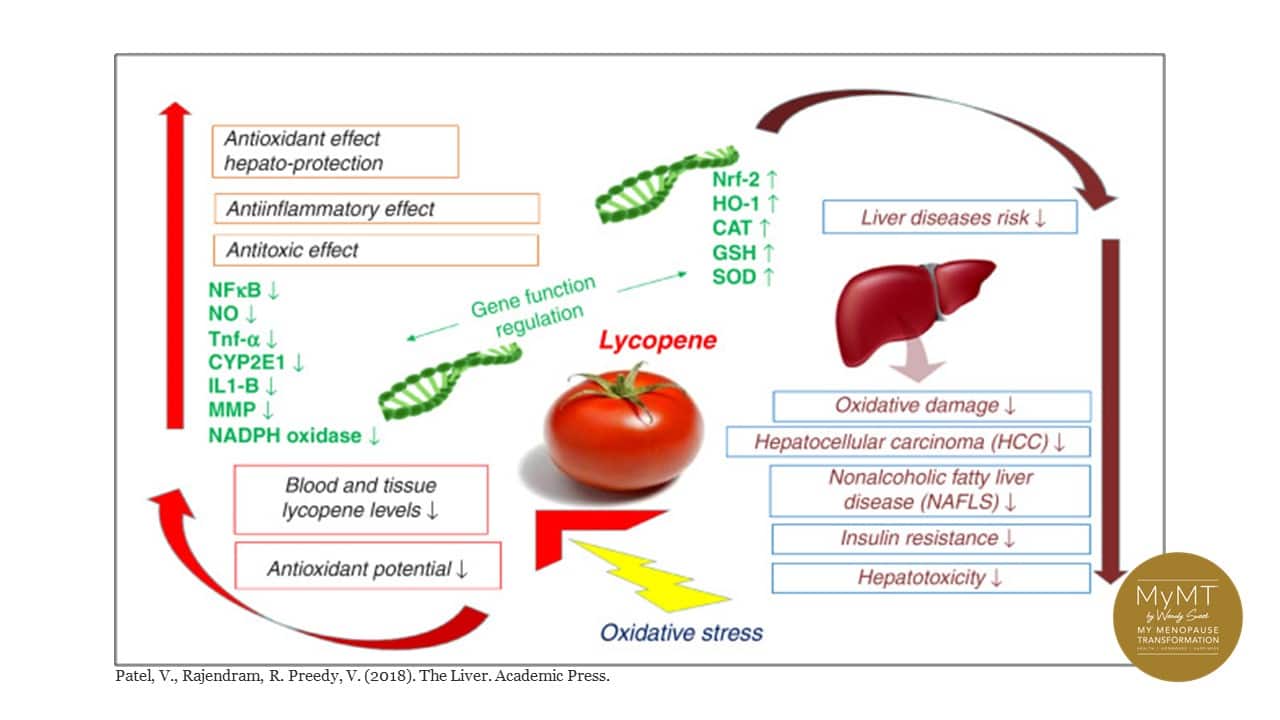

One of the compounds that come in foods that help our liver to ‘detoxify’ is a compound called lycopene.

I’m sure that you know that Lycopene is a naturally occurring compound that contributes to the red colour of fruits and vegetables, including blood oranges and grapefruit. But it’s what the lycopene does inside our body that women’s health and ageing scientists are discovering, that is helpful for all of us to know in order to help our clients succeed with menopause weight loss.

Lycopene is a carotenoid antioxidant – these are fat-soluble pigments of plant origin that are made by plants and help to reduce inflammation inside human cells and tissues. This type of inflammation is known as oxidative stress. Plants which grow above ground and conduct photosynthesis are generally rich in carotenoids.

Humans don’t produce carotenoids, hence dietary sources are important. for distribution to blood and tissues, including the liver (hepatic) and fat cells. However, these powerful compounds play an important role in the production of retinol (vitamin A) and of course, in cell protection.

The role of lycopene in tomatoes and other vegetables and red coloured fruits.

Lycopene plays an important role in weight loss, hot flush management, heart health and improved bone density in post-menopausal women. For those clients who also struggle with their liver health and weight, lycopene is also known to help in the modulation of detoxification pathways.

The liver is ageing and changing during menopause and therefore, focusing your clients on ways to reduce inflammatory changes in the liver, as well as clear excess cholesterol and other harmful substances (including excess oestrogen), then improving liver detoxification pathways can be an important strategy for you to recommend.

Reducing the intake of saturated (animal) fat is important, as is adding cooked tomatoes to the diet and other red and orange foods. (Hodges & Minich, 2013; Tokac et al, 2015; Walallawita et al, 2020; Wilcox et al, 2003).

Lycopene is found in high amounts in tomatoes but is also present in watermelons, pink grapefruits, blood oranges, apricots, and pink guavas.

The bioavailability of lycopene is higher in processed tomato products than in unprocessed fresh tomatoes, so your clients can grill them, add them to sauces or make soup or drink tomato juice.

Just be aware that lycopene bioavailability is also affected by processing methods and storage. Improper processing methods, handling, and storage (i.e., exposure to light and oxygen), can degrade lycopene as well, which is why ‘fresh’ and not supplements or powdered lycopene may be best.

The available research also suggests that lycopene-rich foods are needed daily. This is because its important to keep circulating lycopene at a baseline level for optimal storage and concentration. [Naureen, Dhuli et al, 2022].

When women add lycopene-rich foods to their diet, this valuable compound is stored and used in high concentrations in the liver, adrenal glands, and adipose (fat) tissues.

It’s role in these organs is to help to reduce damage from oxidative stress and tissue injury.

Accumulation of excess fat in liver cells and adipose tissue is cited among the major reasons behind tissue dysfunction (Tokac, Aydin et al, (2015) and therefore, weight gain during the menopause transition. Excess fat stored in liver (hepatic) cells, can also contribute to poor gallbladder health called Cholestasis.

Some of you might have heard this term if your clients have had gallbladder problems, because Cholestasis is a liver disease. It occurs when the flow of bile from the liver is reduced or blocked.

Bile is fluid produced by the liver that aids in the digestion of food, especially fats. When bile flow is altered, it can lead to a buildup of bilirubin and this contributes to blocked ducts and even jaundice in those people with underlying liver disease.

If your clients are putting on a lot of belly-fat, and they are feeling bloated and uncomfortable, then they may be on the path towards developing Metabolic Syndrome. This refers to a cocktail of health problems, due to weight gain, including hypertension, high cholesterol and Type 2 diabetes. All of these conditions are often accompanied by poor liver function.

Therefore, getting your clients to increase their Lycopene intake is just one way for you to help them to restore tired, overworked, inflamed liver cells.

When my own weight reached an all-time high as I went into menopause, I was on all sorts of supplements and HRT. But that wasn’t what my ageing liver needed. It needed some lycopene enriched tomatoes and other foods instead.

Middle-aged women are not only bothered by the physical and psychological symptoms of menopause, but are also at increased risk for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), such as central obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes, which, yes, are partly induced as a result of diminished oestrogen production, but as women on my 12 week programmes are also finding, these diseases are also the result of our lifestyle.

Helping your clients to change their lifestyle is the most important role that you have as a Coach. But what is the evidence behind these lifestyle changes? What is the evidence behind strategies that improve weight management during menopause?

These are the questions I asked myself, and the answers and the evidence is now in the MyMT™ Menopause Weight Loss Coach Course for you. This course also includes exercise prescription, so you can explore the Learning Outcomes HERE. I can’t wait to show you the way with your midlife female weight loss clients.

Dr Wendy Sweet (PhD)/ Member: Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine.

References:

Brady CW. Liver disease in menopause. World J Gastroenterol. 2015 Jul 7;21(25):7613-20. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i25.7613.

Fiedor, J., & Burda, K. (2014). Potential role of carotenoids as antioxidants in human health and disease. Nutrients, 6(2), 466–488. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6020466

Hirose, A., Terauchi, M., Tamura, M., Akiyoshi, M., Owa, Y., Kato, K., & Kubota, T. (2015). Tomato juice intake increases resting energy expenditure and improves hypertriglyceridemia in middle-aged women: an open-label, single-arm study. Nutrition journal, 14, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-015-0021-4.

Hodges R. & Minich D. (2015). Modulation of Metabolic Detoxification Pathways Using Foods and Food-Derived Components: A Scientific Review with Clinical Application. J Nutr Metab. Vol. 2015, 760689. doi: 10.1155/2015/760689. Epub 2015 Jun 16. PMID: 26167297; PMCID: PMC4488002.

Naureen Z, Dhuli K, Donato K, Aquilanti B, Velluti V, Matera G, Iaconelli A, Bertelli M. Foods of the Mediterranean diet: tomato, olives, chili pepper, wheat flour and wheat germ. J Prev Med Hyg. 2022 Oct 17;63(2 Suppl 3):E4-E11.

Patel, V., Rajendram, R. Preedy, V. (2018). The Liver, Academic Press. 155-167, ISBN 9780128039519

Petyaev IM. Lycopene Deficiency in Ageing and Cardiovascular Disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:3218605.

Róvero Costa M, Leite Garcia J, Cristina Vágula de Almeida Silva C, Junio Togneri Ferron A, Valentini Francisqueti-Ferron F, Kurokawa Hasimoto F, Schmitt Gregolin C, Henrique Salomé de Campos D, Roberto de Andrade C, Dos Anjos Ferreira AL, Renata Corrêa C, Moreto F. Lycopene Modulates Pathophysiological Processes of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Obese Rats. Antioxidants (Basel). 2019 Aug 5;8(8):276. doi: 10.3390/antiox8080276.

Tokaç M., Aydin S., Taner G., et al. (2015). Hepatoprotective and antioxidant effects of lycopene in acute cholestasis. Turk J Med Sci. 45(4):857-64. doi: 10.3906/sag-1404-57. PMID: 26422858.

Vetrani C, Barrea L, Rispoli R, Verde L, De Alteriis G, Docimo A, Auriemma RS, Colao A, Savastano S, Muscogiuri G. Mediterranean Diet: What Are the Consequences for Menopause? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Apr 25;13:886824. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.886824.

Walallawita, U., Wolber, F., Ziv-Gal, A., Kruger, M., & Heyes, J. (2020). Potential Role of Lycopene in the Prevention of Postmenopausal Bone Loss: Evidence from Molecular to Clinical Studies. International journal of molecular sciences, 21(19), 7119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21197119

Willcox J., Catignani G., Lazarus S. (2003). Tomatoes and cardiovascular health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 43(1):1-18. doi: 10.1080/10408690390826437. PMID: 12587984